Two travel invitations - Oregon & California: August, 2025

Mount Ashland

Kangaroo Lake environs

Golden-mantled ground squirrel enjoying the warmth of the late afternoon sun

Fish Lake trail

Gentiana spp.

Columbia River water sports at Hood River city

Sundown at Kangaroo Lake

Invitation #1: A Special Occasion

We were delighted to receive an invitation to M and A’s wedding in Hood River, Oregon. A’s family are our good friends and we first met A when he was an infant in his mother’s arms. It was a lovely wedding, full of joy, good will, and light-hearted humor. What’s more, we were able to catch up with long-time friends whom we see infrequently.

The Journey

We took two days to drive from the SF Bay Area to the city of Hood River which overlooks the Columbia River. After three days of wedding activities, we started a leisurely return to home. While in Oregon, we spent time near Klamath Falls, and then continued on to friends who live in the Grant’s Pass area. Re-entering California, we tented at Butte Lake in the Lassen National Park and overnighted with buddies who reside in Plumas County.

Both Oregon and California possess spectacular diverse habitats. However, the two States seem different to me and I was keen to better comprehend what Oregon offers. Any journey is enriched if one gains some understanding of the factors that fashion one’s surroundings. We learnt a lot and thoroughly enjoyed the outing.

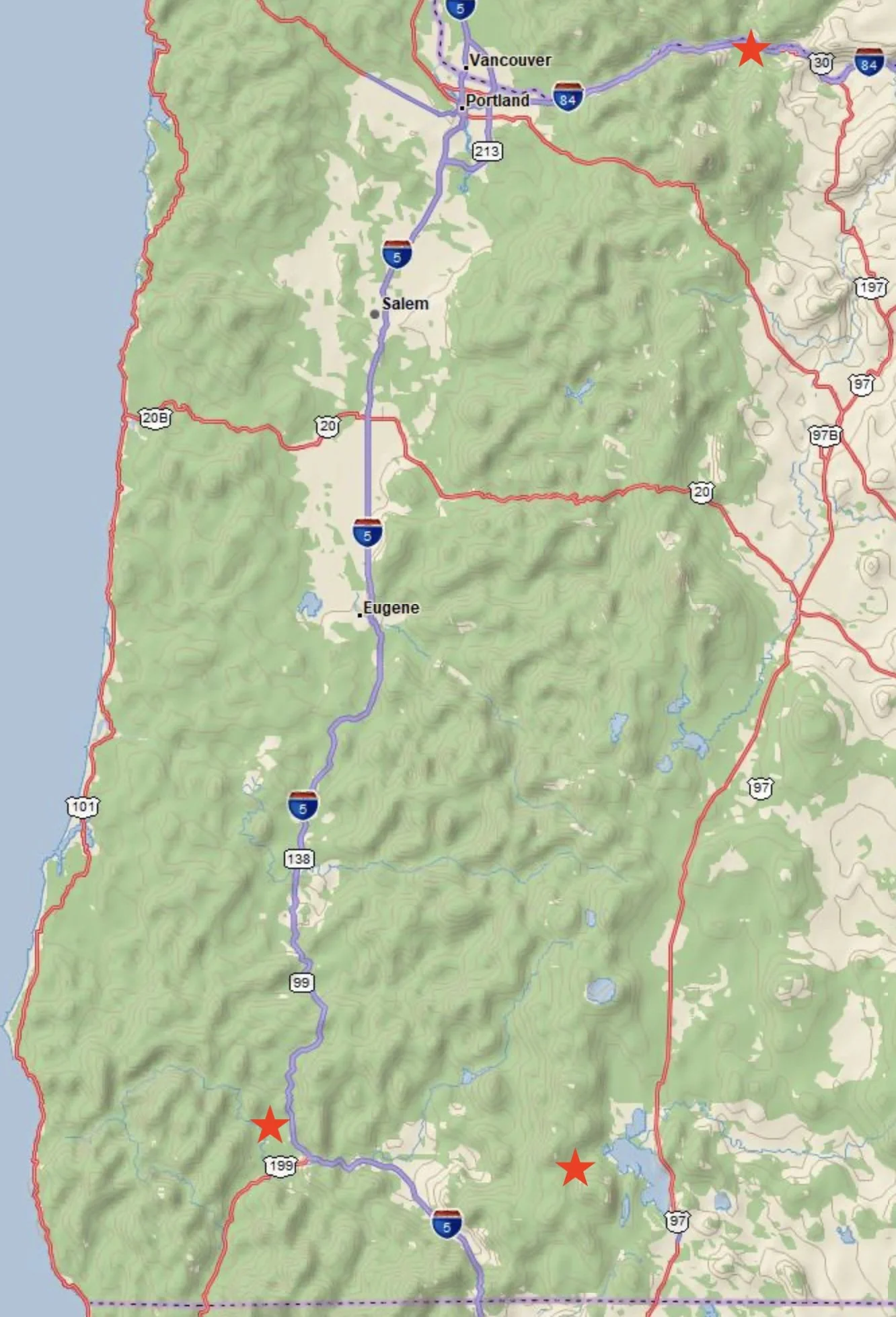

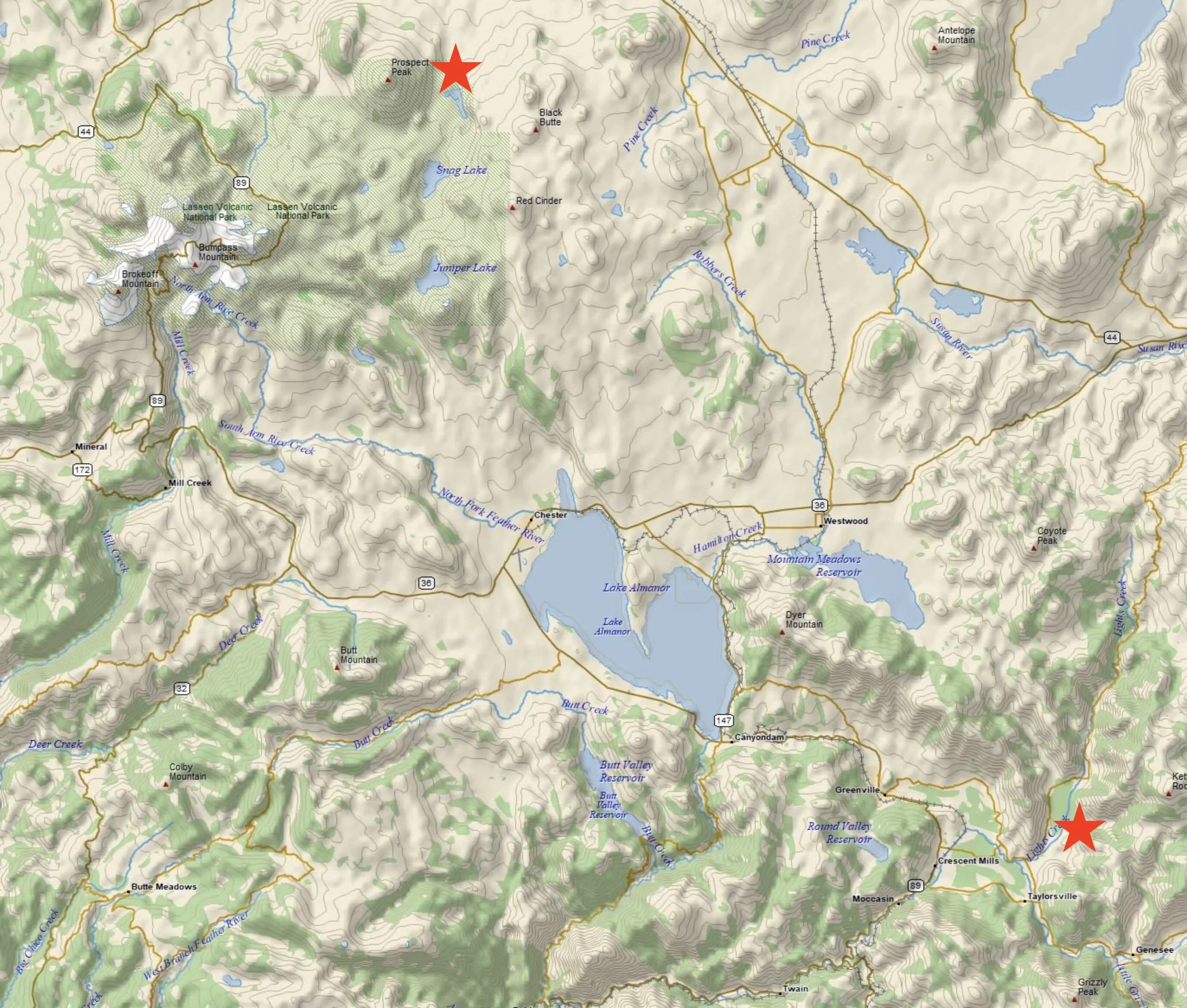

(Red stars on the maps below indicate places where we stayed.)

Western and Central sections of Oregon

Central section of Northern California

Barge, tug and Stand Up Paddler on the Columbia River

The Columbia River at Hood River

The Columbia River has the greatest flow of any river into the eastern Pacific. Of US rivers, it ranks fourth by flow. It is 1,243 miles long; the Zambezi, for comparison, is 1,599 miles in length.

Movement

The Columbia has endured a tumultuous past, albeit over geological time. During the latter half of the Mesozoic Era (250-66 million years ago), tectonic plate movements had rafted marine volcanic islands together, and with subduction of the ancient Farallon Plate under the North American plate, merged (accreted) these land masses (terranes) onto North America’s western edge, thereby assembling Oregon’s coastline. Plate subduction causes volcanoes. During the Cretaceous Period (145-66 million years ago), these volcanoes were located in central Idaho. The region between Idaho’s volcanoes and Oregon’s coastline was covered by lava flows and eroded sediments. Accretion also caused mountain building along much of North America’s western edge and probably prompted formation of the ancestral Columbia River, which transported sediments to its coastal delta.

Fire

The Cenozoic Era (66 million years ago - present) in Oregon is all about volcanics. Around 54-37 million years ago, the Siletz terrane jammed the subduction process, resulting in a new steeper-angled subduction zone and renewed volcanics that created the Western Cascades range. The Columbia had to thread its way through the mountains to the ocean. Then, 16.8 million years ago, enormous volumes of basalt lava poured from fissures in northeastern Oregon and flooded the landscape. Enough lava, it is estimated, to fill Arizona’s Grand Canyon more than fifty times! The suspected cause is the Yellowstone hot spot - a plume of hot mantle material that melted the overriding continental crust. With westward continental drift, the hot spot now lies below Yellowstone, warming bison herds in winter. Of course, lava flows filled river channels and complicated the course of the Columbia. Oregon’s coastal belt was quite low and lava reached all the way to the ocean. Later, coastal uplift occurred, but the Columbia cut its way through the basalt and continued to empty into the Pacific.

Water

Erosion was greatly enhanced 18,000-15,000 years ago by the Missoula Floods, when a huge ice-dammed lake in Montana gave way. The floodwaters charged across eastern Washington and down the Columbia River. This happened repeatedly during the last ice age, with perhaps as many as 40 episodes of flooding. Many deluges are estimated to have been over 400 times greater than average Mississippi flows. Portland city would have been about 350 feet under water.

Wind

At Hood River city, the steep basalt walls of the Columbia River Gorge are obvious. The Columbia Gorge is the only near sea-level passage through the Cascade Mountains and forms a natural gap flow for air. As wind passes through this constricted area, its speed is accelerated. In summer, the Pacific Ocean creates a high-pressure system, while the hot, dry inland areas to the east create a low-pressure system. This significant pressure difference pushes cool, dense marine air from the west towards the warmer, less dense air to the east. While we were at Hood River, sustained 20 mph wind speeds were present at dawn and continued until late evening. Gusts were even stronger. The east-bound wind opposes the west-flowing river, creating incredible standing waves. It was amazing! These conditions attract wind sports enthusiasts from around the world. Hood River boasts a thriving water-sport industry, involving community support, tourism and new product development.

We spent an afternoon watching the action, with perhaps 50-100 participants on the river.

Upper Klamath Region

The Upper Klamath region piqued our interest for several reasons:

Many Bald Eagles gather there in the winter and the waterways support huge flocks of waterfowl.

The headwaters of the Rogue and Klamath Rivers are close by.

There is a sharp transition from Basin and Range topography to the High Cascades range, offering a broad range of plant species.

Human manipulation of the landscape has been substantial and is, in some cases, now being reversed.

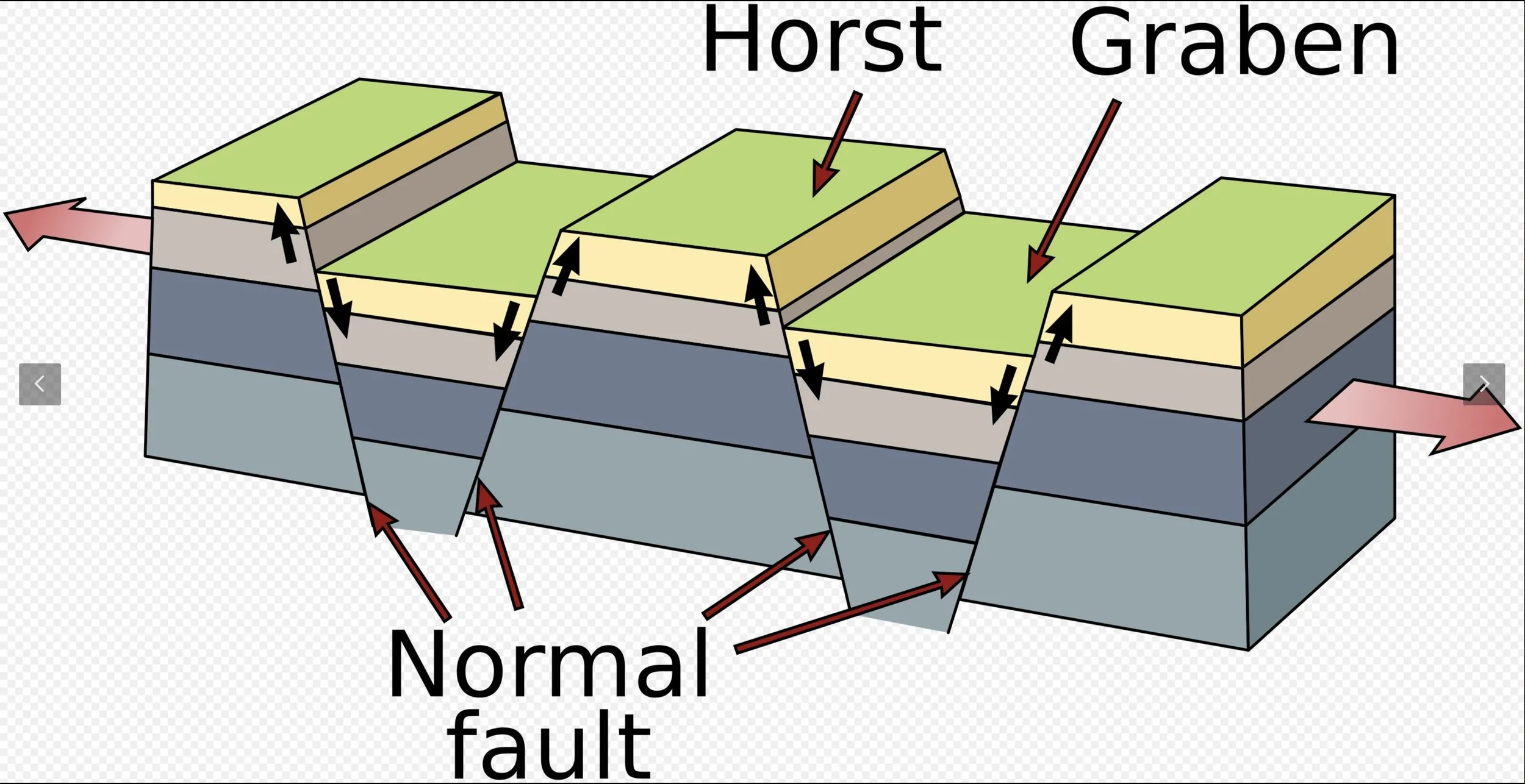

Dip-slip normal fault: a characteristic of Basin and Range topography. (From Wikipedia, USGS)

Upper Klamath Geology

The Klamath Falls area marks the western limit of the Basin and Range Province in Oregon. The topography is described as mountain ranges alternating with desert valleys (basins) and results from crustal extension. Stretching of the earth’s crust leads to normal faulting, which uplifts the ranges relative to the basins. At least three mechanisms are proposed for the crustal extension and they all are present and may contribute. In Oregon, the normal faulting started about 7 million years ago.

Bedrock around Klamath Falls is Miocene basalt. Ash from Mount Mazama (a volcano that violently erupted 7,700 years ago and collapsed to form the Crater Lake caldera) covers the area north of Klamath Falls.

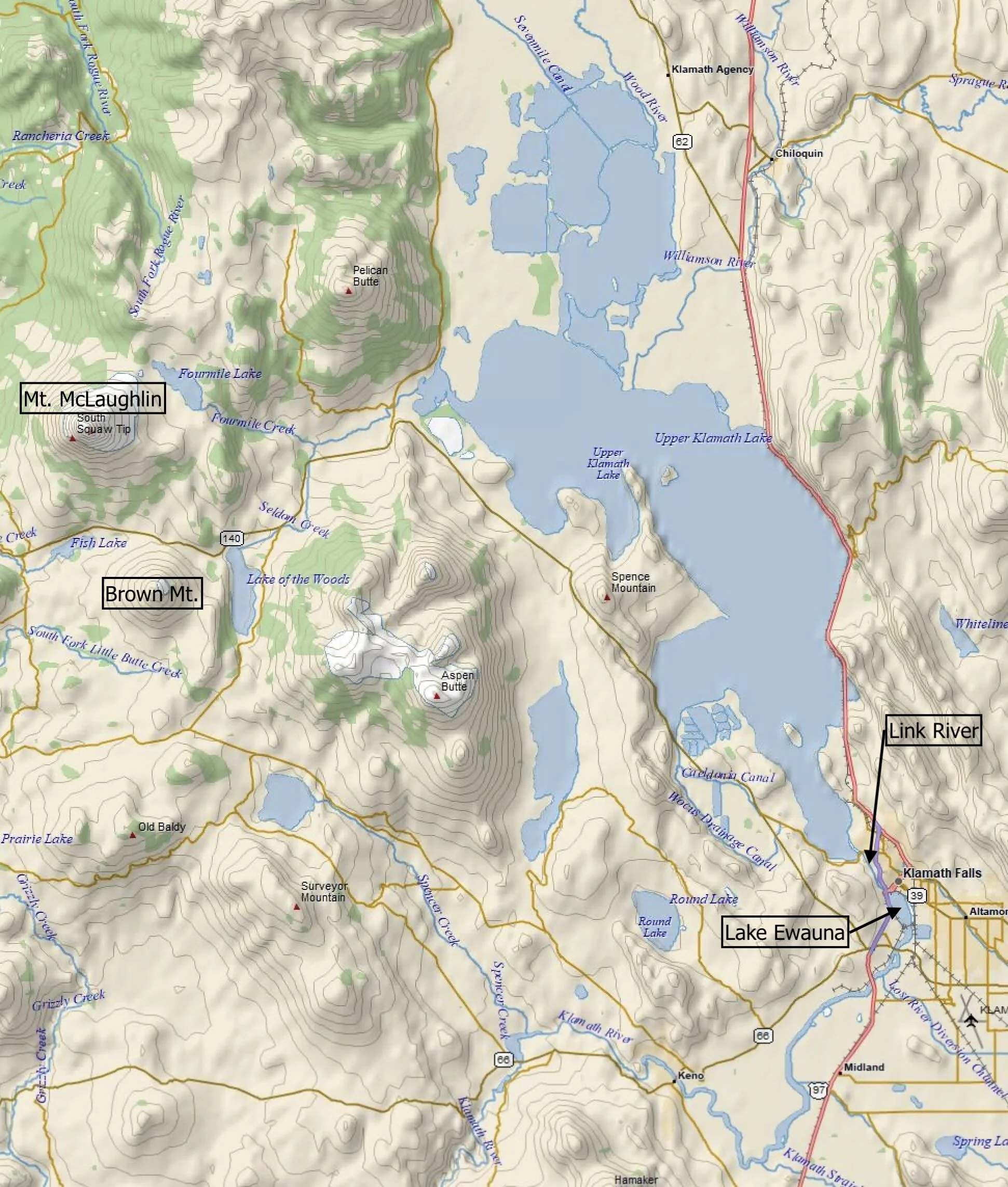

In the wetter and cooler Pleistocene Epoch (2-0.01 million years ago), many of the basins held lakes, some of which were huge. Now the remaining lakes and marshes are much reduced, and have been extensively altered by human management. More than three-quarters of the wetlands have been drained for agriculture. Upper Klamath Lake is mostly fed by snowmelt via the Williamson and Wood Rivers. Link River connects Upper Klamath Lake to Lake Ewauna, a small natural lake that is considered the source of the Klamath River. Klamath Falls city owes its name to relatively minor rapids on the Link River.

Klamath River

The Klamath (257 miles long) and Columbia are the only two Oregon rivers that managed to cut through the rising topography of the Cascades to reach the ocean. The Klamath watershed is known for its biodiverse forests, large areas of designated wilderness, and freshwater marshes. Gold mining and hydroelectric dams had greatly diminished the river’s salmon run. However, after decades of negotiation, four hydroelectric dams were demolished in October 2024, enabling salmon migration to the Upper Klamath Basin for the first time in over 100 years.

Fish Lake

We camped at Fish Lake, a shallow natural lake with rainbow and brook trout that was dammed to increase its size. It is located between two volcanoes - Mount McLoughlin & Brown Mountain; the latter deposited 2,000 year old andesite lava on the lake’s southern shore. Fish Lake spills into Little Butte Creek, a tributary of the Rogue River. We hiked nearby trails, including one that links with the Pacific Crest Trail. In fact, we met several PCT thru-hikers who were obtaining resupplies from the rustic Fish Lake Lodge.

Mount Ashland

Our friends who live near Grants Pass took us hiking on Mount Ashland. Mount Ashland (7,532 ft) is the highest peak in Oregon’s Siskiyou Mountains - a subrange of the Klamath Mountains. The mountain is a 161-million-year old granite, stitching pluton.

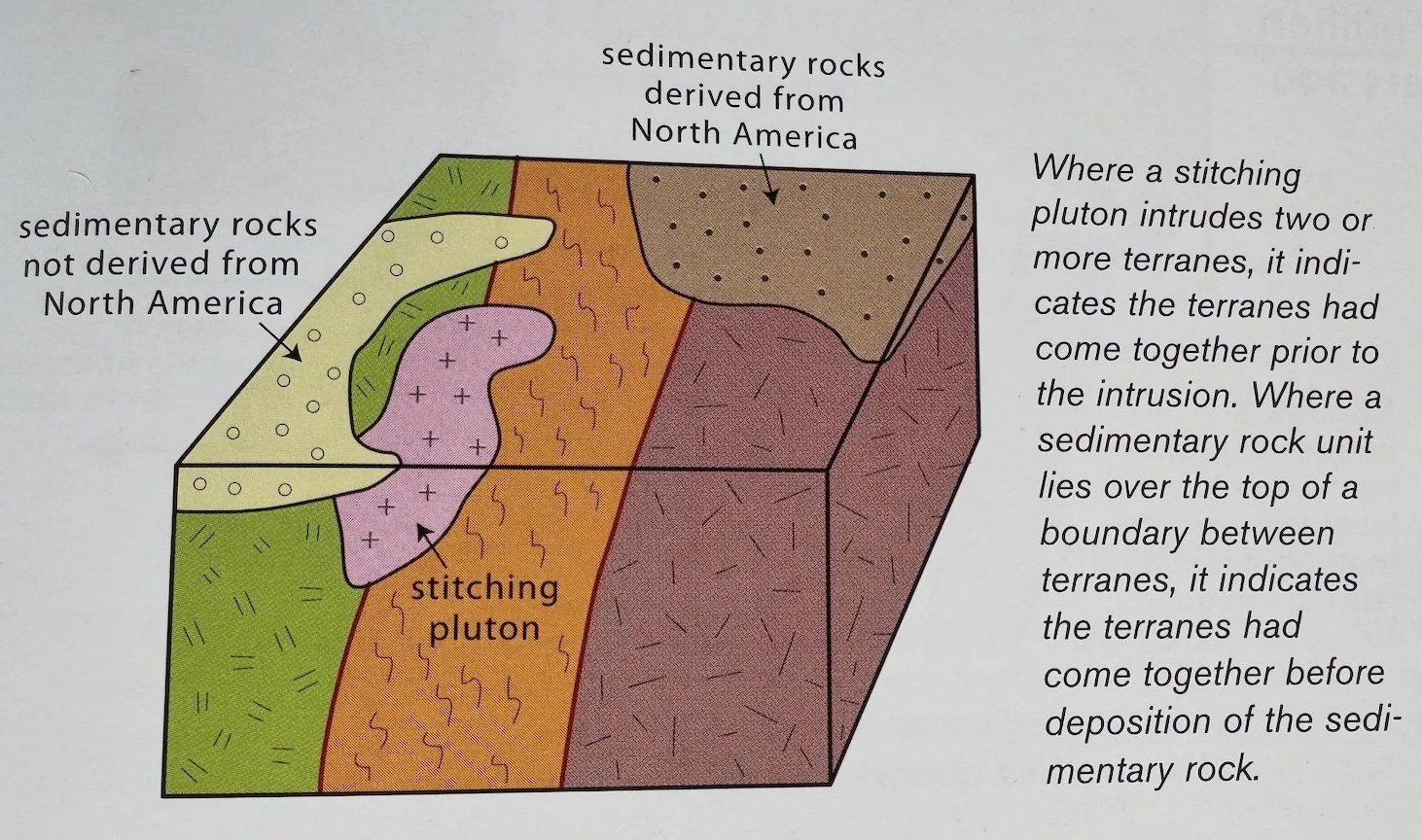

What is a Stitching Pluton?

Many individual terranes merged into larger composite terranes before they accreted onto the North American continent. Evidence for merging of terranes comes from the arrangement of intrusive or younger sedimentary rocks relative to the terranes. Where an intrusive body cuts across the boundary between two terranes, it implies that the terranes were joined prior to the intrusion. These intrusions are called stitching plutons. In the Klamath, most are Late Jurassic and Cretaceous in age (165-66 million years ago).

(From: Roadside Geology of Oregon, MB Miller.)

Which Klamath Terranes?

Mount Ashland lies close to the Hayfork and Rattlesnake Creek terranes that belong in the Paleozoic-Triassic Belt group of accreted terranes. The Hayfork terrane includes oceanic rocks (sandstone, chert, limestone, basalt) from the late Permian to Triassic Periods (260-201 million years ago). Some of its Permian fossils lived in the ancient Tethys Sea, in the vicinity of today’s Mediterranean. They have travelled a long way!

The Rattlesnake Creek terrane includes serpentine and ultramafic rocks from Permian and Middle Jurassic time. The terrane was likely a chain of volcanoes.

By physically intruding across the boundaries of the pre-existing terranes, the Ashland pluton acted like a massive geological "seam" that fused them together.

Lassen Volcanic National Park

Lassen Peak, viewed from the Cinder Cone near Butte Lake. Tree loss from the Dixie Fire of 2021 is evident.

Lassen Peak

Lassen Peak is a 10,457-foot lava dome volcano. It is the southernmost active volcano in the High Cascade Range, and part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc that stretches from southwestern British Columbia to Northern California. Lassen area volcanism has been present for at least 3 millions years, and typically follows a trend of intermittent, episodic eruptions punctuating long periods of dormancy.

Maidu, an enormous volcano, was active perhaps 2 million years ago. It collapsed into its caldera during a great eruption. About 600,00 years ago, Brokeoff (also called Tehama) volcano grew in Maidu’s caldera, and it too collapsed during an rhyolite eruption some 350,00 years ago.

Lassen Peak’s lava dome rose from Brokeoff’s caldera about 27,000 years ago. A lava dome is a circular, mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. The characteristic dome shape is attributed to high viscosity that prevents the lava from flowing very far. Lassen dome consists of dacite, a pale variety of andesite that is very sticky because it has a high silica content.

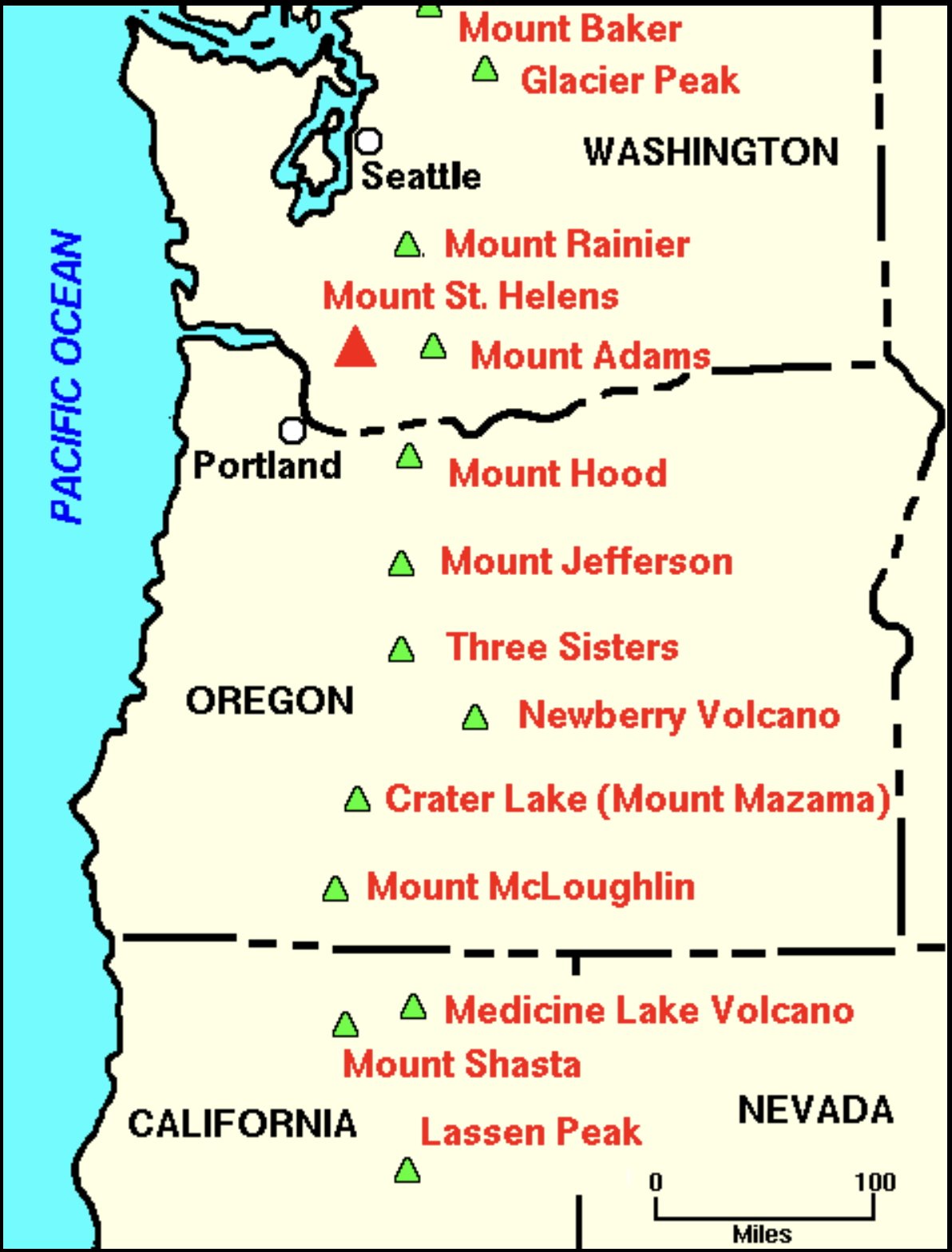

Cascade Range

Subduction zones create magmatic arcs that run parallel to the subduction zone. Modern magmatic arcs consist of chains of volcanoes on the plate overriding the subduction zone. Ancient magmatic arcs appear as the deeply eroded roots of the volcanoes (intrusive igneous rock).

The Cascade magmatic arc extends some 600 miles and parallels the Cascadia subduction zone, created by the Juan de Fuca Plate (a remnant of the Farallon Plate) sinking below the North American Plate. The map indicates some of the significant High Cascade volcanoes in the USA.

The Cascade Range in Oregon consists of two parts:

The Western Cascade formed 40-5 million years ago and is located quite close to the coastline. It formed when the subduction induction angle was relatively steep. These dormant volcanoes are heavily eroded and low lying.

The High Cascade is younger (started about 3 million years ago) and lies to the east of the Western Cascade. It formed when the subduction angle was relatively shallow. Many of the volcanoes are high peaks and some are active today.

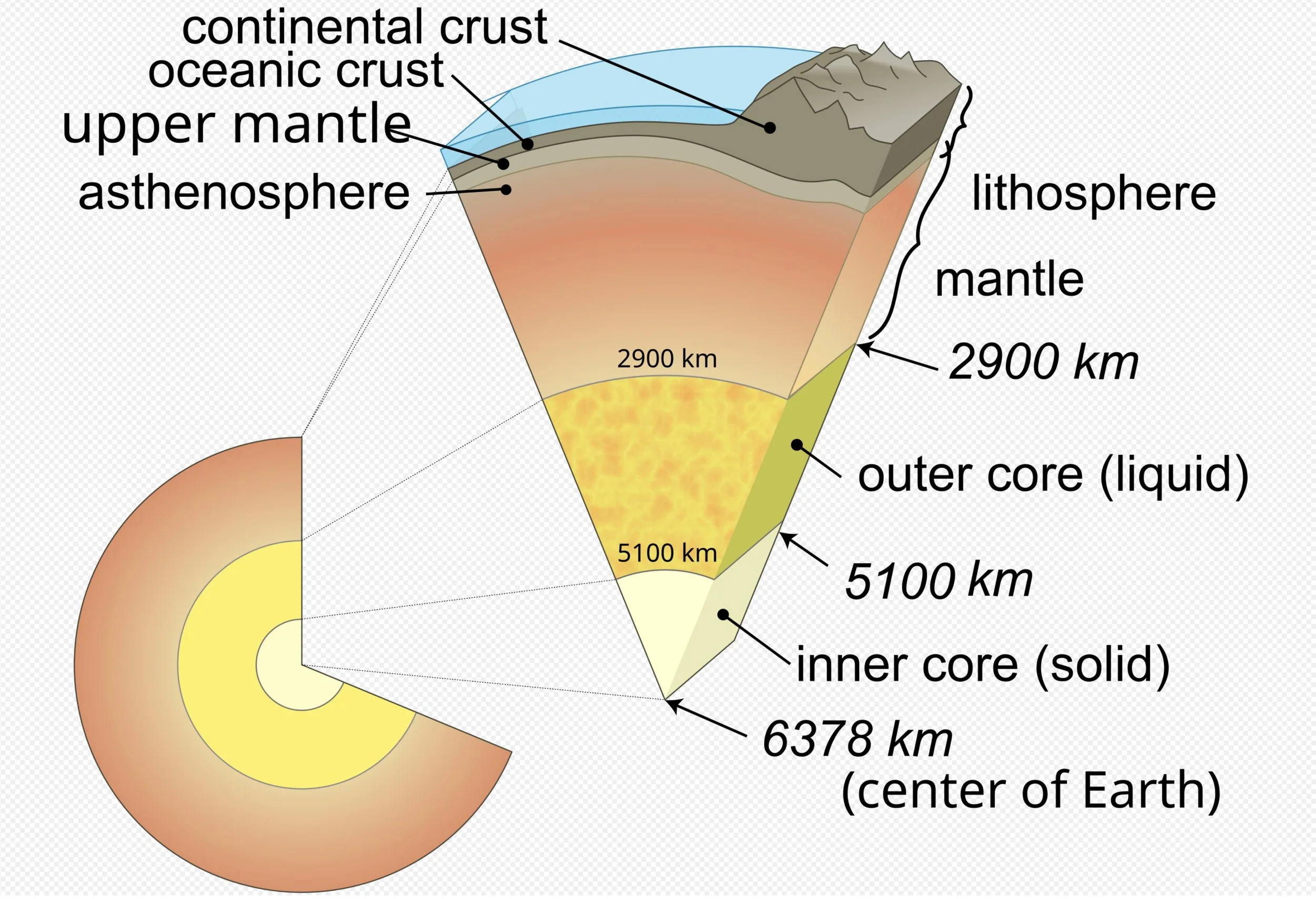

Magma

As the cold oceanic plate descends during subduction, it becomes hotter, causing water-rich minerals to dehydrate. The released water rises into the overlying continental lithosphere. (The lithosphere consists of the earth’s crust and the solid uppermost parts of the earth’s mantle.)

Wet rock melts at lower temperatures than dry rock, and the continental lithosphere at these depths is hot enough for wet melting but not hot enough for dry melting. When the dry rock comes in contact with the ascending water, it starts to melt and form magma.

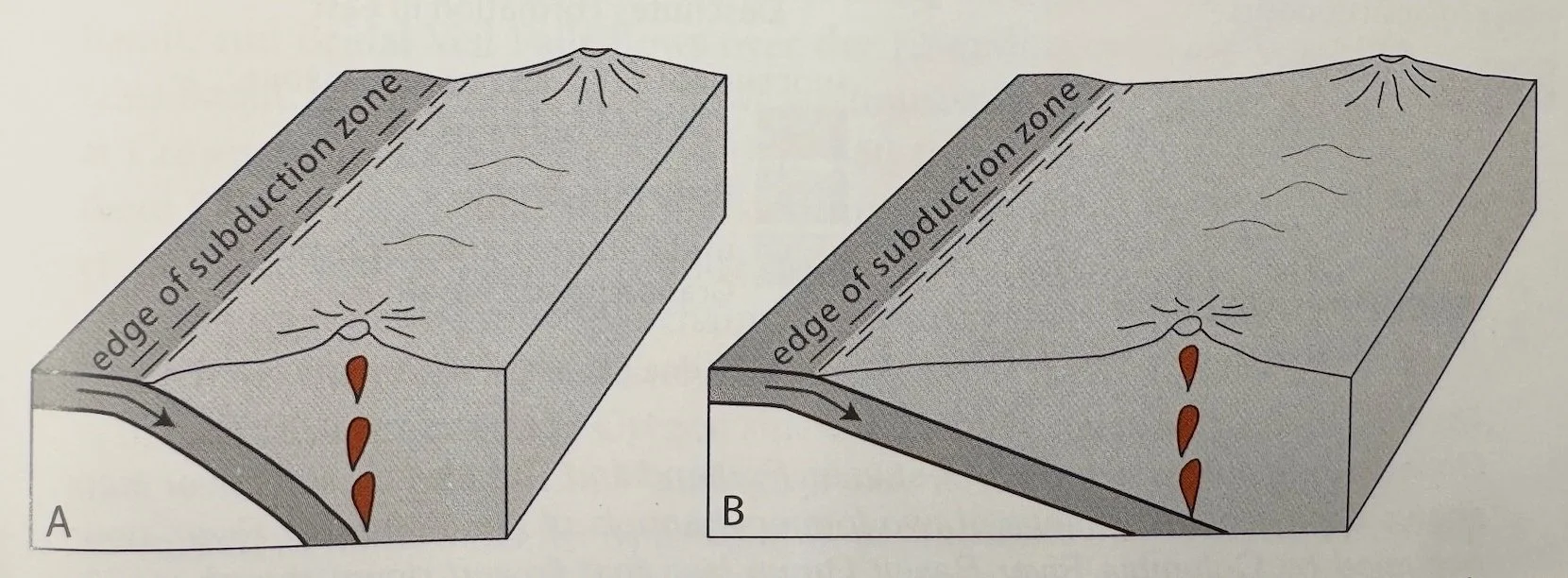

Subduction angle

The location of the magmatic arc relative to the subduction zone depends on the subduction angle of the oceanic plate. If the subduction angle is shallow, the oceanic plate will have to travel further to reach the depth & temperatures that will dehydrate rock and initiate magma formation.

The High Cascades (smaller angle, figure B) are further from the subduction zone than are the Western Cascades (larger angle, figure A).

Butte Lake

Our camp was within the Lassen Volcanic National Park at Butte Lake campground. We swam in the lake, explored our surroundings, and hiked to Cinder Cone. The tent was situated among tall conifers that seemed almost Jeffrey pine or almost Ponderosa pine. Turns out they were probably Washoe pines, which closely resemble both Jeffrey and Ponderosa pines. Some authorities regard Washoe pine as a Ponderosa variant. Others recognize it as a separate species. Regardless, the trees were beautiful, and emitted a sweet vanilla fragrance.

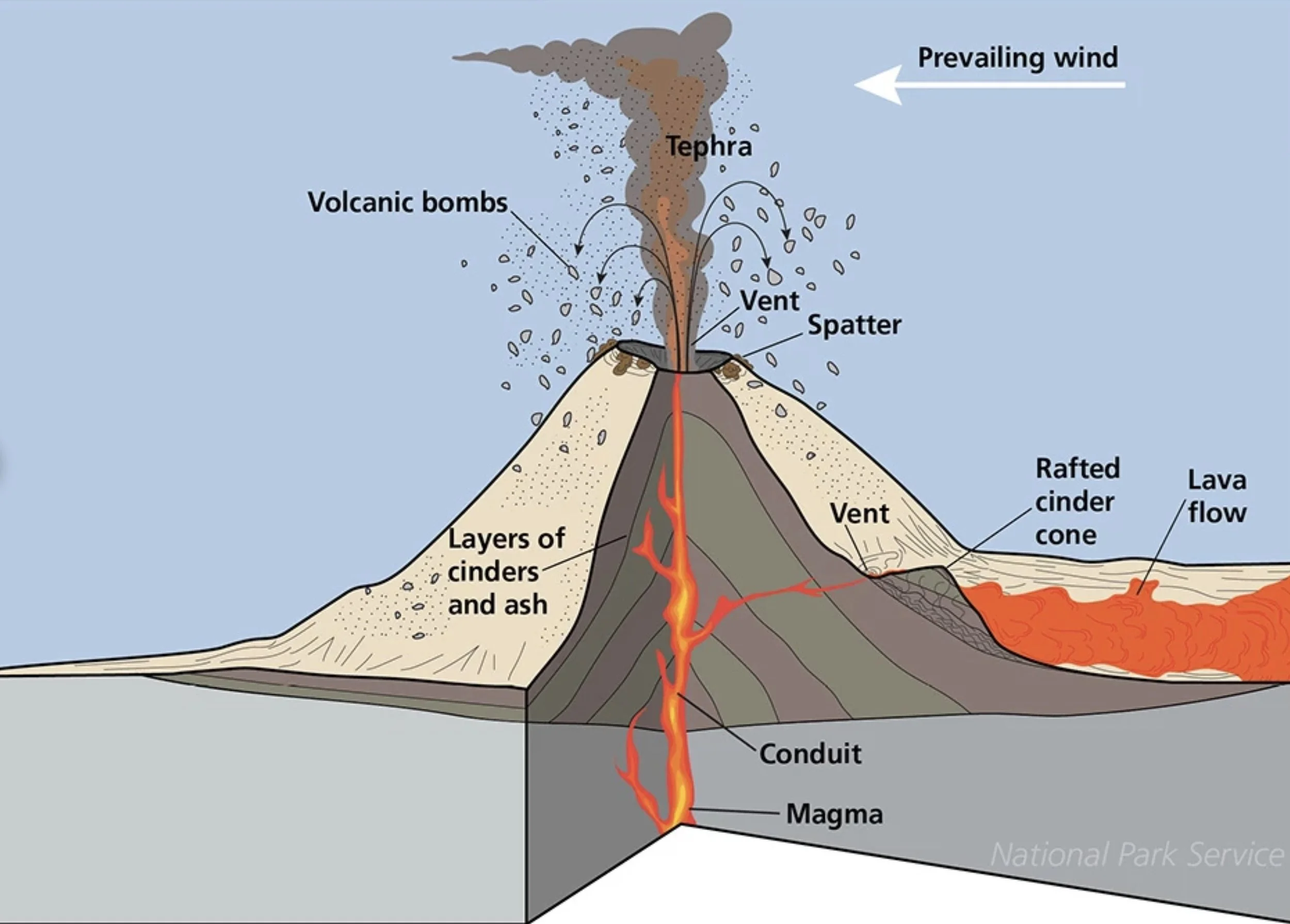

Anatomy of a cinder cone

Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds

A cinder cone is a steep, conical landform of loose pyroclastic fragments that has been built around a volcanic vent. The pyroclastic fragments are formed by explosive eruptions or lava fountains from a single, typically cylindrical, vent.

As the gas-charged lava is blown violently into the air, it breaks into small fragments that solidify and fall around the vent to form a cone that is often symmetrical, with slopes between 30° and 40° and a nearly circular base. Most cinder cones have a bowl-shaped crater at the summit.

The pyroclastic material making up a cinder cone is usually basaltic to andesitic in composition. It is often glassy and contains numerous gas bubbles "frozen" into place as magma exploded into the air and then cooled quickly. Lava fragments larger than 2.5 inches across, known as volcanic bombs, are also a common product of cinder cone eruptions.

During the waning stage of a cinder cone eruption, the magma has lost most of its gas content. This gas-depleted magma does not fountain but oozes quietly into the crater or beneath the base of the cone as lava. Lava rarely issues from the top because the loose, uncemented cinders are too weak to support the pressure exerted by molten rock as it rises toward the surface through the central vent. Because it contains so few gas bubbles, the molten lava is denser than the bubble-rich cinders. Thus, it often burrows out along the bottom of the cinder cone, lifting the less dense cinders like corks on water, and advances outward, creating a lava flow around the cone's base. When the eruption ends, a symmetrical cone of cinders sits at the center of a surrounding pad of lava. If the crater is fully breached, the remaining walls form an amphitheater or horseshoe shape around the vent.

Invitation #2: Come for a Hike!

J & B are veteran hikers. They invited a group of botany-minded friends (including us) to join them on a multi-day backpack trip to Mount Eddy. We had just returned from the trip to the Hood River wedding, which made it easy to repack for camping and slip back into the travel mode.

Mount Eddy is part of the Klamath Mountain Geomorphic Province and is the highest peak (9,037 feet) in the Trinity range. It is located about 10 miles west of Mount Shasta. Shasta is a tall (14,179 ft), majestic, snow-clad stratovolcano of the High Cascades. Mount Eddy is nothing like that. It is rounded, ruddy, affable, and atop the first and oldest Klamath accreted terrane - the Eastern Klamath. The rock is Mesozoic ultramafic, predominantly serpentinized peridotite. It formed deep in the ocean floor and is loaded with iron and magnesium. Certain plant species have evolved to tolerate the harsh conditions typical of serpentine soils, - heavy metals, low calcium, drought, & poor nutrient retention.

Mount Eddy is of particular botanical interest because of the soils, and is designated as a Research Natural Area. There are 8 rare plant species, with the foxtail pine (Pinus balfouriana) considered especially important. Trevlyn is, at the moment, enthralled with buckwheat, (genus Eriogonum, in the family Polygonaceae). This species-rich genus is different from the buckwheats of Europe, and approximately a third of Eriogonum species are uncommon, or threatened. Mount Eddy is well-endowed with buckwheat, including rare species such as the Trinity buckwheat (E. alpinum) and the Siskiyou buckwheat (E. siskiyouense).

Eriogonum species are used as food plants by the larvae of some butterflies and moths. Several of these Lepidoptera are monophagous, meaning their caterpillars only feed on this genus, sometimes just on a single taxon of Eriogonum. In some cases, the relationship is so close that Eriogonum and dependent Lepidoptera are in danger of coextinction.

We established camp at Deadfall Lake, hiked to Eddy’s summit while clouds coalesced and thunder rolled, and went south on the Pacific Crest Trail. Earlier, in Oregon, we met north-bound PCT thru-hikers, now we encountered several heading south. Generally, they seemed to be enjoying their epic undertaking.

Washoe pine

References

Information was obtained from:

The Klamath Mountains, a Natural History. M. Kaufman & J. Garwood

Roadside Geology of Northern and Central California. D. Alt & D.W. Hyndman

Roadside Geology of Oregon. M.B. Miller

National Parks websites

Wikipedia

Calflora

US National Forest literature

AI did not write this blog. I am responsible for errors.